TENDERNESS IN BLACK FILM

A Black Film Archive exhibition“Love ain’t what it is. It’s easy to fall in love, but will someone, please, tell me how to stay there?” -Love Jones (1997)

INTRODUCING TENDERNESS IN BLACK FILM

What are the social consequences of aesthetic control over our image-making? From Frederick Douglass to Ava Duvernay, the question has been posed by Black intellectuals and artists across time. In response to the denial of Black humanity by white stereotypical mythmaking – the coon, the jezebel, the tom, the mammy — embedded into white cultural production, Black thinkers, writers, and artists suggest that controlling Black imagery is essential to imagining Black humanity and futures. As Douglass writes, “The process by which man is able to invert his own subjective consciousness into the objective form, considered in all its range, is in truth the highest attribute of man’s nature.” Imagery, then, must be the foundation of progress when we take it into our own hands.

In the February 1926 issue of Crisis Magazine, W.E.B Du Bois poses ‘a questionnaire’ to the magazine’s readership about the ways Black people are represented in art. “What are Negroes to do when they are continually painted at their worst and judged by the public as they are painted?” the pioneer scholar asks.

That question is echoed in the post-George Floyd Black audience that asked if Black films’s only offering is trauma. This ponderance is the tenant to which the Black Film Archive: Tenderness in Black Film exhibition responds directly. How does tenderness– defined here as pointed moments of affection where Black possibility, transformation, and connection bloom– offer a new mode of understanding our filmic past, present, and future?

![]()

As pioneering Black film director Oscar Micheaux writes, “I have always tried to make my photoplays present the truth, to lay before the race a cross section of its own life, to view the colored heart from close range.” In this close read, new truths about Black cinema and ourselves are revealed.

Personifying love allows us to awaken the senses and endlessly discover ourselves, our communities, our beloveds, and our families; it is the building blocks of life and I argue, an essential way to engage with Black cinema. Tenderness is what spurs motion into movement, desire into affirmative risk, and improvisation into rhythm. For Black people, I believe, tender gestures give us the will to live, to carry on, to pursue in a world that wants otherwise or life presents other obstacles.

Personifying love allows us to awaken the senses and endlessly discover ourselves, our communities, our beloveds, and our families; it is the building blocks of life and I argue, an essential way to engage with Black cinema. Tenderness is what spurs motion into movement, desire into affirmative risk, and improvisation into rhythm. For Black people, I believe, tender gestures give us the will to live, to carry on, to pursue in a world that wants otherwise or life presents other obstacles.

Sometimes tenderness is a glimpse from one Black person to another, conveying a lifetime of knowledge or a warning to choose another path. Tenderness can be confronting what is unseen or unspoken within ourselves or it can be a director giving language to the beauty of our world, our pioneers, and our lives.

![]()

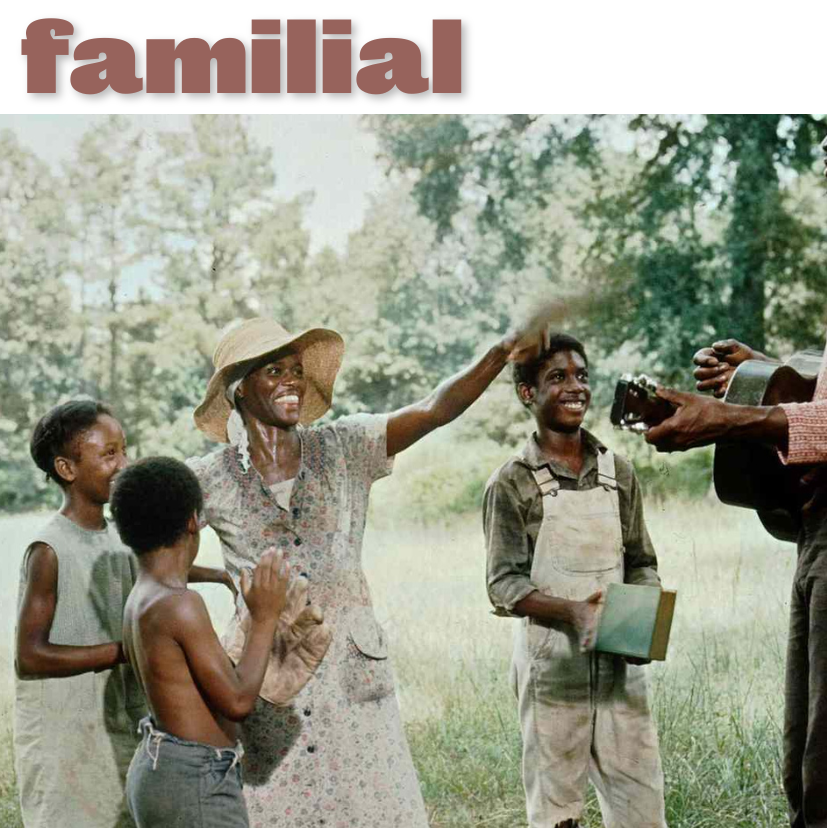

This exhibition, organizing tenderness through familial; community; romance; and self & soul connections are in conversation with the desires planted in our lives at birth: to dream of a world of love and care; to give voice to those who have been silenced or torn from the pages of history; to believe in Black futures enough to will the impossible into existence; to not abandon ourselves and others out of fear. May we learn to say things without words, embrace ourselves and others with tenderness, and run to all gentleness that approaches with care and allow cinema to be a guide when we cannot trace the impulses alone.

Tenderness in Black Film, which will be updated on an ongoing basis, is simply a place to begin. I hope you’ll join me on this journey. The research in Black Film Archive: Tenderness in Black Film was funded by a residency at the Library of Congress.

This exhibition, organizing tenderness through familial; community; romance; and self & soul connections are in conversation with the desires planted in our lives at birth: to dream of a world of love and care; to give voice to those who have been silenced or torn from the pages of history; to believe in Black futures enough to will the impossible into existence; to not abandon ourselves and others out of fear. May we learn to say things without words, embrace ourselves and others with tenderness, and run to all gentleness that approaches with care and allow cinema to be a guide when we cannot trace the impulses alone.

Tenderness in Black Film, which will be updated on an ongoing basis, is simply a place to begin. I hope you’ll join me on this journey. The research in Black Film Archive: Tenderness in Black Film was funded by a residency at the Library of Congress.